Master Fantasy Artist’s Memorial Event From 3-7 PM, Saturday, March 26; Open For All Who Wish To Honor Him, His Life And Works

By Larry Freeman

When most folks cross through the silver doorway to face the silver ball inside the Pacific Pinball Museum, they usually think of the surrounds as an artifact arcade or spot steeped in the history of pinball.

Many don’t see it –at least not initially– as an art museum replete with numerous works of original art that adorn the walls and glass window surfaces of the interior.

One quick look at any of the expansive10’ x 10’ canvas hangings emblazoning some of the wall space makes clear that PPM is also an art gallery flush with original paintings, whether on canvas or wall stucco.

Among PPM’s corps of highly talented artists, the standout, in PPM founder Michael Schiess’ view, was Ed Cassel who passed away at age 77 on January 8th of this year and for whom the Memorial Celebration is dedicated.

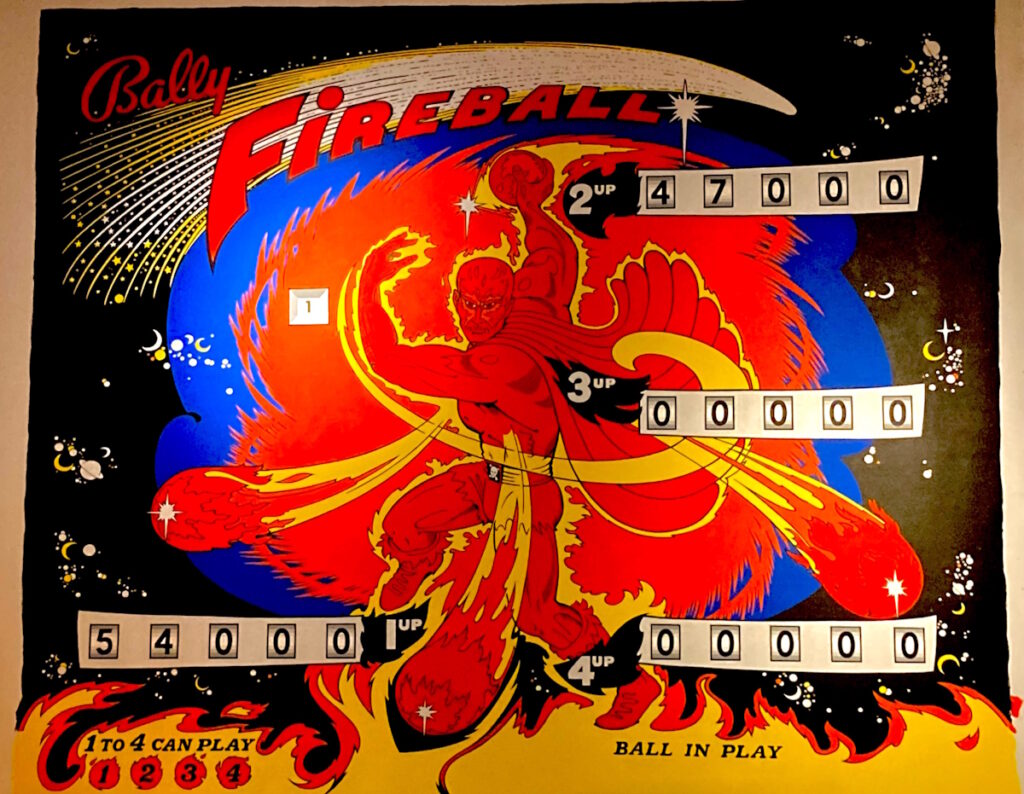

“You can see the difference in his paintings,” said Schiess, remarking on Cassell’s massive pinball back glass replications.

“His stuff is really tight. He was ‘Mr. Precision’. It looks like it comes right off the playfield” or scoreboards that are the two main display media of pinball artistry.

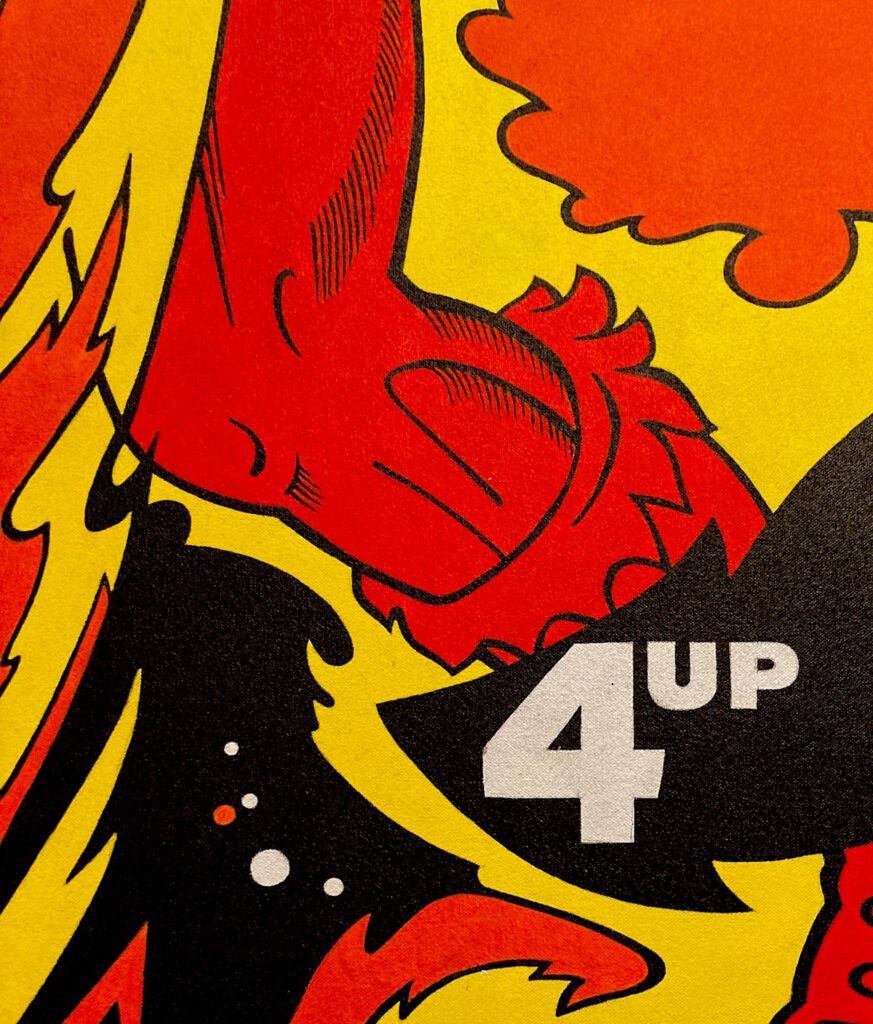

Two photos of a part of the “Fireball” backglass. Image to left is from the actual game. To right is Cassell’s near identical rendering. (photos L Freeman)

But Cassell was not just a duplicator of master level accuracy, as Schiess well knows of his life long friend and on and off long term roommate who became a kind of art docent for Schiess, who first me him at age 18 in 1972.

Cassell was a creative, imaginative force in his own right, said Schiess. “He paints by feel,” he said, pointing out one of Cassell’s many, wild, fantasy world creations.

Titled “Grand Cavern,” the work was a multi setting based hybrid poster style piece inspired by the natural, “muted psychedelic” environs of an airbrushed celestial galaxy in the night sky.

In the foreground, one peers out of a Carlsbad Caverns mouth into the Grand Canyon unfolding just outside. Somewhere in the mélange Cassell also managed to add in a ship in a bottle.

Sadly, the original piece. commissioned for a mere $300 for replication into posters by Berkeley’s now defunct Print Mint, met a dissembled end: Cassell cut the piece up into small squares for use in an Edgar Allen Poe inspired creation he envisioned in his burning brain.

Schiess still has what may be the only remaining piece of the work. “He cut it up. He cut it into pieces,” sighed Schiess with a touch of remorse, before moving back into what inspired Cassell’s artwork.

“He always required reference materials and always used them,” said Schiess about “Grand Cavern” and Cassell’s Poe themed creations.

Cassell might spend hours in a library or poring through all kinds of art environs to find the nugget image that would spark a notion.

–Six of Cassell’s original Poe works, cherished keepsakes of Schiess, will be on display at the memorial exhibit.

At an early point in their relationship, Schiess, seven years the younger, bristled at Cassell over a joint project involving the painting of crystals.

Schiess brought forth some photos, but Cassell demanded real crystals that would fit the still developing vision he had in mind. Cassell had to have the actual artifacts and nothing short would do.

“Well what do you need those for?” asked a stymied Schiess. “Just paint the thing. And the project just fizzled.”

Cassell’s quest to capture the world to the satisfaction of his mind’s eye did not fade or fizzle, however.

“He had an almost obsessive fascination with Edgar Allen Poe. In between jobs, Ed would draw upon Poe’s stories to guide his imagination, said Schiess.

Six of Cassell’s original Poe works, cherished keepsakes of Schiess, will be on display at the memorial exhibit.

But it was not so much the desperate, dark side of Poe’s psyche that inspired Cassell as much as it was the tantalizing lure of that inner fantasy world, and that impelled him to seek out as much as he could in that great expanse of artistic creation.

“He was fascinated with Ray Harryhausen,” said Schiess referring to the famed, monster film animator whose fantasy world work on Sinbad films or “The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms” set the tone for Casell’s inspirations.

The 1961 Canadian surrealist, horror film, “The Mask,” in which a psychiatrist dons ancient Aztec or Mayan mask and has horrific visions of the walking dead, and other dark doings, also tantalized Cassell’s inner psyche.

That fascination with fantasy realms fed Cassell’s fancy for Pinball art, notably the massive back glass murals on canvas he created.

Ever prolific, Cassell produced about 30 of the huge, portable, pinball themed works on commission from PPM, and “we finally had to stop the project. It got hard to find space,” said Schiess.

That includes the vast expanse of PPM’s warehouse as well as the museum itself where many still drape the building’s vast interior.

While on might simply regard them as replica renditions of someone else’s artistry, the murals are anything but when it comes to how Cassell went about creating them without veering from his inner mandate for precision.

He would start by projecting a copy of the back glass using an opaque projector to get a template to exactingly outline all the black lines in the piece. “That would take about two or three days to do, “ said Schiess.

Next, Cassell would divide the piece into grids, so that each part would be used as a miniature version of what he would paint on the massive sheet of canvas has he projected, one square at a time, onto the surface

What came next were two or three months to replicate the black lines on ‘the screen’ to be filled in with the manifold complex colors that are part of the original back glass.

It was kind of like paint by the numbers,” said Schiess.

But Cassell did not at all march to the drum beat of numbers outside of his commercial work, nor did his mind operate in any grid like fashion.

Early in his friendship with Schiess in the early 1970’s when the two lived together in New Mexico, bonded by their pinball buddy-hood, Cassell tried his hand as a film maker, taking a blank, transparent length of 16mm film leader to which he applied “black crackle paint,” said Schiess.

When the paint did its thing, the images resembled a fractured, madly oscillating black and white desert mud hard scape . Cassell added a soundtrack of heavy rainfall and “It was mesmerizing,” recalled Schiess.

The work might have been a kind of homage to the pioneer French animator, Emile Cohl, generally credited as having created the first animated work, “Fantasmagoria” in 1908.

But most of Cassell’s artistic bent drew him to the paint medium.

But whatever he worked on was still an extension of his artistic passion and creative drive.

PPM, acting as a patron of the arts, kept Cassell solvent as a sort of resident PPM artist with monthly commission payments and a cottage in Berkeley to live in to keep him on task of creating numerous canvas back glass murals

When it came to working on the murals, the replicative task and laborious process showed another part of Cassell’s artist’s DNA, a near compulsion of perfection of line, color, proportion and all the other elements that go in to making a mural rendition of a pinball back glass.

“He needed that reference,” said Schiess, referring to people who are concert pianists but can’t play without the sheet music before them. But with Cassell, whatever the notes on the page were before him, “He made it his own.”

For him the sheet music was that crystal from bygone days which he ultimately had to make his. “ He put his own personal rendition on it”

That was the case for the last two paintings Cassell made before debilitations of Parkinson’s disease impaired his long time abilities to paint.

His last two pieces, 4’ X 8’ panels of Egyptian Hieroglyphics and a rendition of an ancient Greek rendition of Apollo and his horses stand as a kind of metaphor for Cassell’s life and who he was.

Just as his did as a young man with the crystal project , Schiess was puzzled at his solemate’s conceptualization. Why are you doing that,” asked Schiess.

He picked a weird subject –well, weird for Ed.”

But in the end, it was really just what it had always been, true to his own artistic compass.

Ed generally didn’t do anything he didn’t want to. He just did those for himself,” Said Schiess.

To the left, the actual back glass of the game. To the right, Cassell’s handcrafted mastery on canvas. (Photos by L Freeman)

===============================

FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT PPM AT 510 769 1349 or email to info@pacificpinball.org

| PACIFIC PINBALL MUSEUM MEMORIAL INVITE The museum will be free from 3 pm – 7 pm on Saturday, March 26th and & the memorial will be in the “Replay Room,” the furthest room toward the back of the museum across from the original “Lucky JuJu” room which Cassell inspired. Ed Cassell first inspired Mike Schiess to create the original, miniature version of PPM with the incarnation of Lucky Ju Ju, which Cassell envisioned as a kind of “Gentleman’s Club” for pinheads. “It was anything but,” chuckled Schiess, but it was Cassell’s reminder of that dream, years later, that set Schiess into taking the first steps to create what has grown to become a great recreation spot and remarkable museum.institution for folks far and wide or just here in town. “He never forgot anything,” said Schiess, acknowledging how Cassell’s life now lives on , in part, as an enduring legacy to the benefit of so many. Please come by, say hello and sign the memorial book and play the games that were part of his fascination and consummate craftsmanship |